An Absurd Pastime: A New Perspective on Post-Trail Depression

Pretty much anyone that’s gone on a long hike and come home to an internet connection has made a post of some kind about post-trail depression. My favourites are this article based on interviews with thruhikers by Anne K. Baker and this discussion on r/PacificCrestTrail started by u/meta474. If you’re not already familiar with the concept, it’s a bluesy feeling experienced almost universally by people reintegrating into civilization after spending a few months hiking. It can last anywhere from a few days to a few years.

Because this phenomenon is so widely experienced and discussed publicly online, the most common causes and recommended solutions are widely understood. I’ll start by listing them below just so that we’re on that same page.

| Experience on trail | Experience upon reintegration with civilization – causing depression | Associated recommended treatments |

| Vigorous daily exercise | Relatively sedentary lifestyle | Take up a fitness routine, especially running |

| Sense of purpose and progression towards a clear goal | Lack of drive, confusion about priorities | Avoid unemployment, plan future hikes |

| Constant beauty, nature, peace and quiet. | Too much concrete, noise of cars and the city | Go for dayhikes or walks in a park, move to Colorado |

| Simplicity of lifestyle | Paying taxes, making plans, choosing outfits | Pursue minimalism, move into a van |

| Close-knit social life with like-minded hikers | Urban isolation, complex social situations | Stay in touch with hiking partners |

And I think that’s all good stuff, really. The depression-causers and associated advice are cliche for a reason: as I said, they’re nearly universally experienced. But the thing that was gnawing at my own pursuit of happiness as I finished up my thruhike of the Pacific Crest Trail in 2019 was something a little different from what most hikers talk about. I wanted to write in this post about my own take on one of the fundamental causes of post-trail blues, because I haven’t heard or read this take on it yet. And to clearly set the stage for what I’m talking about, I need to take you to my last day on trail that summer.

The Final Day

From the start of my journey, I knew that I wanted to challenge myself physically. The idea of a 100-day thruhike, a relatively moderate challenge in an average year, bounced around my head as an appealing potential accomplishment. But as I slowly trudged through the record-breaking Californian snowpack, I began to question whether the 100-day goal was even possible at all.

I progressed northwards through the summer with the days ticking down like a doomsday clock towards my self-imposed deadline. And at the end of it all, I found myself crawling out of my sleeping bag in the early morning of August 17, 2019 with 60 miles (96 km) between me and the Canadian border and only 24 hours left in my 100-day countdown.

How could I resist? It would be my longest day of hiking by a long shot, but not impossible, I knew. I packed my gear up just like I had 99 days in a row, not really taking the time to notice that it would be the last time I went through this familiar routine. After studying my maps up to where they ended at the end of the country itself, I walked, watching the world go by at the rate of 3 miles per hour that all thruhikers feel oh-so at home with.

I walked without stopping from dawn to dusk, as I had pretty much all summer. But then I kept going even after the light from the setting sun faded and my world shrunk down to only as far as my headlamp could shine. Even when I ran out of real food, I kept walking, powered only by cake frosting and cold coffee. I passed tents filled with sleeping hikers and passed the curious eyes of unidentified nocturnal animals.

My feet started to blister, my eyes grew heavy, the midnight rain soaked through, and my headlamp battery slowly faded. But still, I kept walking, my mind made up that this was something I would finish tonight.

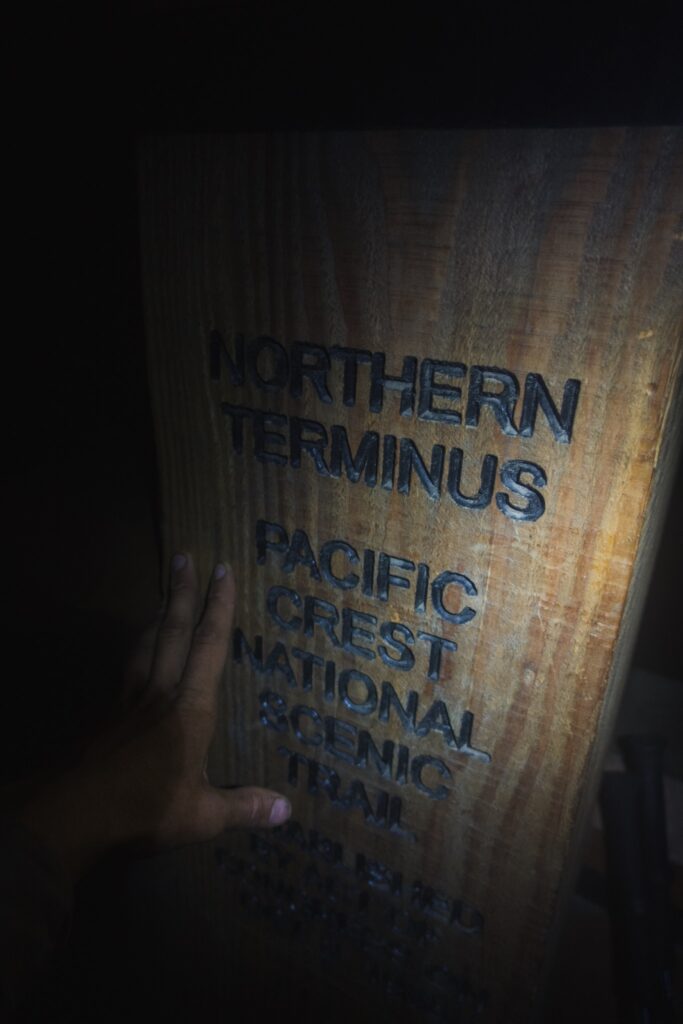

And eventually, in the dim pre-dawn light, I finished. At those wooden pillars I had daydreamed about every day of the last 100, I finished hiking for the night but also for the summer. My instinct when I first saw the monument was anxiety. What was I supposed to do?

But anxiety gave way to joy, relief, and sadness. What a confusing feeling. Not bad or good, just a lot. Anyway, I collected myself, walked the remaining eight miles (not even an official part of the PCT, but they still had to be hiked) to the highway and hitched my way home to reintegrate into society.

The Questions

Depending on what type of person you are, you probably think I’m fairly stupid or kinda awesome for making that overnight 60-mile push. Either way, we can all agree that it was a pretty absurd thing for me to do. After all, 100 days, other than being a nice-looking round number, is an entirely arbitrary time goal, not inherently more meaningful than 101 or 102 days. So why put myself through so much discomfort in pursuit of it?

A good answer to that question eluded me in the days after finishing. And I think that part of the reason I didn’t know the answer is that I was scared to think about it too hard. Part of me was scared that if I questioned my motivations for that big day of hiking, I would run out of answers and realize that there really was no point to it.

Thing is, while I didn’t know what the point of it was, I know I followed through with it and I know I would do it again. And where things got really worrisome is when I followed that line of thinking to it’s inevitable conclusion: if hiking has no point, and I do it anyway, then what’s the point of anything?

If I can push myself through 24 hours of sore feet, hunger, sleep deprivation, and rain without really knowing why, am I doing something comparable with the rest of my life? Is the daily grind of wake up, work, eat, sleep existence just as absurd as walking all day and night? Do we just slog it out until the end of our lives the same way I didn’t stop walking until I hit the terminus?

If I can walk from Mexico to Canada without a real reason, why not just walk out into the ocean, too?

After I finished my thruhike, I spent my first few days resting and recovering, getting ready to reintegrate into civilization. At that point, all those questions nagged at me, ushering in feelings of pointlessness and depression.

The Answers

I didn’t know the answers. Some people have some solid belief systems in place, like a relationship with God, to deal with those questions. I don’t have that.

And while this might sound like a downward spiral of uncertainty that leads nowhere but darkness, it’s not. Because although I was having trouble figuring out why I decided to walk across the country in 100 days, there were a few things I did know: I enjoyed the heck out of that final day, my loved ones and peers told me it was inspiring, and it felt so, so good.

What set me on the path to answering those questions started with a quote by Bill Bowerman, the co-founder of Nike and legendary running coach. Here, he’s talking about running, but I think it applies just as well to hiking:

“Running, one might say, is basically an absurd past-time upon which to be exhausting ourselves. But if you can find meaning in the kind of running you have to do to stay on this team, chances are you will be able to find meaning in another absurd past-time: life.”

Bill Bowerman

Even if I started my hike without really knowing why, and even if I walked all through the night without a good reason, I do know that it made me feel joyful and satisfied down to my core and sharing my story has apparently done some good for other people too. In my whole adult life, I’ve rarely felt as happy, confident, and ready to make a positive impact on the world as during my summer on the PCT. And if that’s not meaningful, I don’t know what is.

Reintegration

If we take Bowerman’s advice, those of us that have taken on the difficult, absurd task of walking across the country are only one step away from leading a deeply meaningful life, something that can be elusive to those of us that don’t think God put us here. Although there’s no good reason for us to be alive in the first place, same as there’s no good reason to start walking north from Campo, we create those reasons through our own progress up the trail and through life with our own actions and how we affect those around us.

The wonderful people I met, hard work I put in, and beautiful landscapes I saw are what eventually gave my hike meaning where there was none to begin with. Those experiences were only possible because of the work I put into my journey, and they took on a whole extra level of intensity because I did it all within a time goal that I found to be meaningful for me. I eventually came to realize that there was no reason I couldn’t achieve comparable feelings in my life after the trail.

If I could take on the day in my civilized life with the same drive and openheartedness as I did my life on trail, things would be all right, and they would be meaningful. But it would up to me to put the work in to allow that meaning to manifest, because it wasn’t going to be there on its own.

If you’re feeling like getting out of bed and this whole life thing is a little pointless, just try to remember what that pointless walk across the country meant to you and maybe you’ll find some answers to get you where you need to go.